“The Artist that smells squeaky-clean is most likely a Spy” – AA Bronson

‘Art’ does not exist outside of society, communities and institutions. Any artist operating under the notion that they can completely transcend these structures is mistaken. Artistic work is made possible by support systems and platforms that all have real sources in the world. As a country that supposedly values Art (and certainly profits from it), the places that we fund to house art are supposed to encourage and mobilize it. As an artist, I want to examine and question these art centres and systems, not only to see if they are doing what they are supposed to but figure out how I can navigate and use them to share my own artwork. What does a thriving arts community look like and what are the systems that make it possible?

Becoming part of the ‘Art World’ is daunting. To show in large public galleries like the Art Gallery of Alberta, an artist must have an impressive amount of experience under their belt. Universities offer expensive degrees in studio art and curate campus galleries. When applying for grants, prerequisite experience and a clear direction with your work is expected in order to receive one, as well as an ability to write well. All these standards are in place to ensure that the Art that is supported is of high quality, critical, well-thought out, etc. But how does one come to produce high caliber art? Why does there seem to be little network for visual artists in Edmonton outside of large institutions and commercial galleries? Is there not some place where artists go to experiment, to join forces with a community, to make a mess, to gain momentum, to take to the streets (legally)? I dream of being involved in a visual arts community that I can actively contribute to. It is more important to me that the work I make can live a brief life than reach some impressive ‘pinnacle’ of career after decades of institution-climbing. These places are, in my mind, what would make for a lively Edmonton arts scene. This got me thinking about getting involved with an “Artist-Run Centre”. I decided to go to Vancouver which has more ARCs to get a better idea of what it is like to contribute artwork to a community without a fancy resume.

Image Source : http://arcpost.ca/images/15.jpg

Image Source : http://arcpost.ca/images/15.jpg

There is a simple answer to why Vancouver has more arts happenings than Edmonton does. For one thing it is the second most densely populated city in Canada. Whatever you want to say about the art scene in Vancouver, there have simply been more people there, and therefore more art. Every city has its own dynamics when it comes to the Arts community, but maybe it was good to explore Vancouver as a visitor. I could enjoy being the outsider looking in. Becoming an expert or having a complete picture of visual art scenes is impossible. All I can do is have conversations, move like a human thermometer passing through places, and quilt together a patchwork of understanding. As much as I wanted to see how artist-run centres serve the function of mobilizing artists’ practices, I was testing my own nostalgic ideas of what living and working as an artist looks like. Was I clinging to ideals of arts collectives that were outdated and unsustainable, or was I just not hip enough to be in on one? Did I need to get with the Neoliberal agenda and focus on commercializing my work? Was a place like Vancouver better equipped to support a vibrant arts ecology than Edmonton? Am I just lacking in my ability to create happenings by my own sweat and blood? These were all thoughts I took to the streets to have scuffed, bruised and tested.

I have always romanticized Artist-Run Centers as free radicals, but the Canada Council for the Arts has a very specific definition of what they refer to as ‘ARCs’. ARCs are thought of as a ‘parallel- gallery’ system. They were born as a way to escape the limitations of traditional gallery models, filling the gigantic void between commercial galleries (motivated by profit) and public galleries (that tend to be weighed down by an overarching mandate for the ‘public good’ and the need to adhere to established structure). They first formed in the 70s by groups of artists who banded together in DIY initiatives, set off by our southern neighbours who were raising the vibrational frequencies of art at that groovy time. Canadian artists then felt that there wasn’t space for more experimental work in established venues and they decided to advocate for themselves. Their original motivation was to create “resistance to a culture in which their work was improperly contextualized, ignored or devalued” (Shier). They rented the space or property they could get their hands on and set up shop with a loose mission: clearing space for new ideas.

Plaque of Support in VIVO

The formation of ARCs was made possible by a new national funding model introduced in the seventies. Most of the ARC funding comes from the public sector, and ARCs require public funding to be realized. If the government were to cut all funding to ARCs, it is easy to see them disappearing in their current form. Artistic autonomy, not profit, must be at the heart of ARCs, and this would not be possible while needing to appease the interests of business investors. Although ARCs were invented to meet the needs of artists, the government now recognizes them as an essential form of artistic distribution and the term ‘Artist-Run Centre’ has come to represent a specific type of artistic gathering. They have become part of a bureaucratic system. Funding depends on meeting certain requirements that are used to define ARCs. In other words, far from every artistic movement and initiative in Canada falls into the category of ‘ARC’. DIY projects and those without a traditional or critical artistic discourse are not eligible to be ARCs in the eyes of the CCfA. It seems that the term ‘ARC’ has become for the government an easy way to generalize and regulate the funding of ‘alternative’ artistic practice. Although ARCS originated out of liberation from categorization, they cannot escape it now.

In order to receive funding from the CCfA , ARCs must:

+ maintain a permanent space or office accessible to the public

+ have maintained an annual program of artistic activities, accessible to the public, for a minimum of three years in a row

+ Pay professional artists’ fees to artists participating in your organizations programming activities (fees must meet or exceed the national standards)

+ Be incorporated, non-profit and registered in Canada

+ Be directed by a board composed of a majority of practicing visual artists and have a principal mandate to encourage research, production, presentation, promotion and dissemination of new works in contemporary visual arts.

(Canada Council for the Arts, 2011)

Throughout four decades ARCs have been greatly influential, living up to their utopian ambitions of blowing open the possibilities of artistic production. The conception of many alternative practices that are now part of the mainstream took place in artist-run centres such as intermedia, performance art, feminist art, etc. Most of the widely known or influential artists and curators Canada now boasts got their start in ARCs (PAARC, 2014). It can be easily said that much of the ‘meat’ in Canada’s artistic content fattened its substance in underground communities, and without grass-roots developments it is hard to see how larger, better-funded and more stable Institutes of Contemporary Art could have anything relevant to fill their walls with. It is important to acknowledge the feeding that has taken place over time from the experimental workings of small-scale communities to grand stages of international repute. Keith Wallace, former curator of the Contemporary Art Gallery in Vancouver, clarifies the role of artist-run centres in Canada’s cultural ecology : “artist-run centres are on the bottom-rung of the art gallery hierarchy and produce strong, dynamic programs with relatively few resources” (Tayler, 2005)

We now live in a world where multi-national corporations quite frequently co-opt and sell back the symbols of marginalized groups in contrived aesthetics that seem to separate their products from the rest of the market (think of hip hop and graffiti to sell computers, ‘hand-crafted’ drinks at coffee-shops, ‘haute-goth’ at department stores, etc.). It would be interesting to see what they would have left to sell if the ‘heart, soul and guts’ of cultural production became completely homogenized. In short, there may be no perfect model for a critical, independent arts space, but the vitality of culture depends on them existing in some form, and much profit has been made off the freshness of ideas coming out of them. It is not hard to see how the forging of artist-run centres has made possible a lot of this vitality from which we still benefit.

Front door of James Black Gallery, Vancouver

(not officially considered an ARC)

Despite how ARCs have thrived in their day, it is not the seventies anymore and many people working in fine arts have noticed that ARCs are moving away from their radical histories, and towards professionalization. Reid Shier observes this trend thoughtfully in their article,” Do Artists Need Artist-Run Centers?”. Despite being called “Artist-Run Centres”, the oldest ARCs are now run by curators and directors, not artists. Much of this is due to the increase of graduates coming out of post-secondary curatorial studies programs who see artist run centers as the perfect vehicles for their achievements (although even when artists acted as curators, biases and similar processes of selection still took place). With space becoming more valuable and harder to access, this trend of ARCS to hire non-artist administration staff and adapt a more structured model allows them to secure their place in a climate where professionalization can come with status. Shier notes, “Artist-run centres helmed by non- artist curators could be seen as a win-win situation. In one model of institutional growth, a developing artist-run centre with committed long-term professional staff may see necessity in graduating to a larger public gallery.” Some cultural workers, like an administrative staff member I spoke with at the Contemporary Art Gallery, see this is a natural progression of an organization with clear, long-term goals. The Contemporary Art Gallery started as an artist-run-centre, but has now evolved into an Institute for Contemporary Art, accessing the more secure resources that come with their new status.

The Contemporary Art Gallery in their space specially designed by an architect for their purposes.

It makes sense for ARCs that have been credited as such to further develop their establishment and allow for more predictable space and programming. However, some argue that this removes their critical or radical edge and makes them comparable to other institutions, discrediting their function as ‘parallel galleries’. One concern expressed by arts professor Bruce Barber is that, ‘”the more structure (a gallery has), the less internal potential for change” and that the future of critical, challenging, artist-run projects may have to lie completely outside ‘white cube’ models of the gallery. To even achieve the initial demands of certification, an ARC must receive a lot of funding internally which could from-the-start sabotage it as a distant and fresh alternative to an established gallery. I am also concerned that the pressures of needing to conform to a prim and proper government agenda has transformed the original idea of what an ARC is ‘supposed to be’, but without support from some sort of funding body, ARCs are impossible to forge from scratch. This leads me to believe that the way we fund ARCs, if a critical/experimental role is what we intend them to fill, should be unbiased enough to allow for a broad variety of forms that they may take, and supportive enough that they can be possible.

One cannot deny that art is alive (and well?) in Vancouver. It was easy to pick up on some new ideas on my trip to YVC. Vancouver in the Summertime is a constant flurry of happenings. I arrived early August, right between the Feminist Electronic Art Symposium, the Vancouver Outsider Arts Festival, and the International Bird Parade, all of which would have been amazing to check out. In fact, while searching for Centre A gallery in a random Chinatown building I stumbled into a brand new non-commercial gallery I didn’t even know existed called the SUM gallery. Through word of mouth I’ve since heard of countless other projects happening in Vancouver, a lot of them passing under the radar and the most-travelled path. I can only imagine the countless artistic happenings taking place invisibly or outside of government funding models.

Artspeak Gallery in Gastown

Prior to arriving I pictured ARCs as shopfronts you could just walk into and see an exhibition on that day. Amazingly enough, a lot of them are. Many ARCs occupy a space on a typical city street, only instead of glossy ads in the windows, the spaces themselves tend to look like blank canvases. A perfect example is Artspeak in Gastown. The content of what is inside is not revealed by the neutral facade. I can see many passers-by being unsure as to what they’re getting into when they walk in the door. The Gallery Gachet can confirm that much of the daily audience of these central galleries is just made up of people passing by on the street, curious about what is inside. I like this idea, of the occupation of a typical office building or shop in the name of art. It feels like a breath of air in the typical industrial sandwich of a busy street : a bit of poetry slotted into the standard syntax.

Gastown is Vancouver’s oldest, and one of its most lauded neighbourhoods. For some organizations it is not easy to hold down such prime real estate. The unfortunate reality of art spaces is that they’re constantly forced to get up and relocate (you can see this in Edmonton where arts venues are evicted down the road from the sign that reads ‘Arts District’). Still, it is especially important for these places to be somewhat central so that they can be accessible and active within the immediate community. It is hard to get people out to shows if they must travel 3 hours across town to see them, and it is hard to reach a ‘general’ audience in a suburb or a warehouse. Keep in mind that ARCs also need to maintain a permanent office space in order to earn funding, so snagging a premium spot is in their best interest.

Artist run centers aren’t the only ones forced to get up and move shop in Vancouver’s hyper-gentrified downtown. A local record store owner explained that often there are odd deals worked out between owners and renters. Some property owners support artistic or charitable causes and will offer more affordable rent, while others will rent a cheap space for a very short lease of only a couple months. Spaces can be hooked up through a friend of a friend or gotten easily if the building is falling apart. Still, settling in comfortably is not a privilege most can count on. In the worst-case scenario, the owner of Lululemon, Chip Wilson, will buy up the building, subdivide it, and double the rent forcing you to leave (which happened to the Red Gate recently, you can’t write this stuff). An Arts center might see their rent doubled down the road from a condo development whose ad is an artsy mural that reads “Curated with a Vision for a Vibrant Culture and Thoughts of Tomorrow.” It was disturbing to see the crushing dominance of privilege that corporate powers can afford in Vancouver. However, it is easy to see how a change in policy could provide solutions. In the best-case scenario the local high rise down the street will be forced by the city to buy and donate rental property to the ARC, providing a permanent home. This is an extremely rare instance that happened for Western Front two years ago. Now that they own their own property and don’t have to worry about being evicted, Western Front is in the situation that the ARC 221A is working and advocating towards for arts organizations: a stable home that is not constantly at risk, allowing for long term planning and programming. The founding members of 221A worked for years before they could start out with a space of their own. It seems that cultural venues in Vancouver are open to coming across stability in whatever way they can manage it.

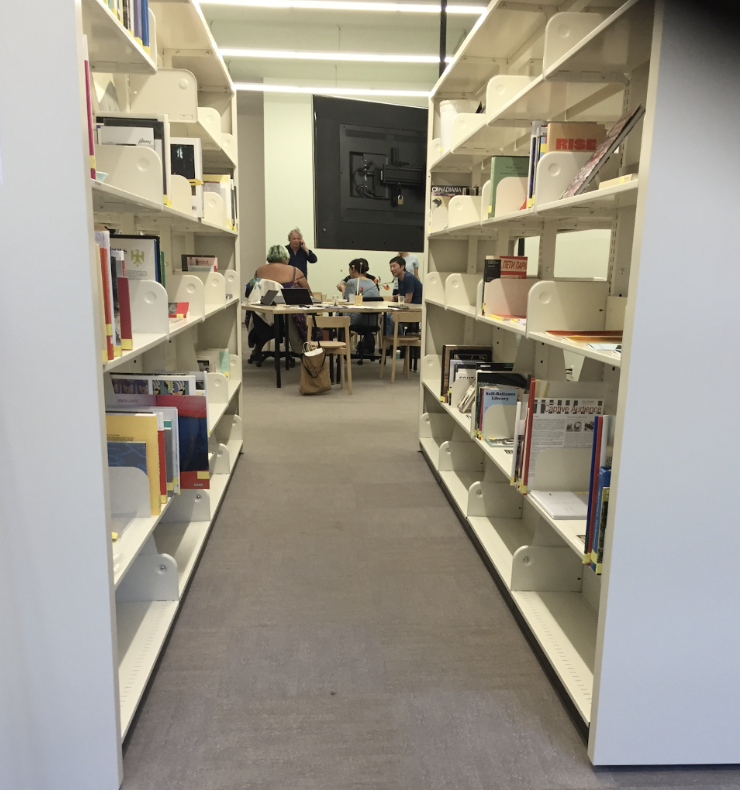

The Pollyanna Library (and the Annual General Meeting) in 221A

It is true that in a fast-paced city there is a high pressure that comes with trying to hold space. At the same time there are just more deals being made and broken in the city in general, and with that a massive circulation of opportunities opening and closing that the resourceful can get their hands on. This is why all sorts of people move to the city: there are more employment opportunities in their field as they are swimming in a bigger pond. Artists might also have a chance to swim between different galleries. It’s not like Prince Edward Island or rural Saskatchewan where if you blow it with the only venue in town, your number is up. I must admit I have given into the romantic notion of the artist struggling to earn their place and it is common sense to me that art spaces might be difficult endeavors to get off the ground seeing as art is not a viable business. However, when we reach the point where having any sort of small-scale art space in a neighborhood is impossible, something is deeply wrong with how we ‘support the arts’ in Canada. If you can only afford to underpay one or two employees, and those people are spending most of their time just trying to keep pace no matter how hard they may try, there is nothing romantic or bohemian about it and this impoverishment will surely be reflected in the artistic work. The ecology of a neighborhood should have some possibility for a speck of diversity to squeeze in, no matter how tight-knit and high profile it has become. Otherwise, if it is completely soulless, what is making it so high profile? The ghost of the myth that great historic events, that rich interactions might happen there? There is a difference between being a starving artist and a person just wasting energy and resources trying to stand up in such shaky financial terrain.

Save-On-Meats restaurant in Hastings, which has previously provided free meals to people in need, has recently opened a tiny slice of their shopfront to a full-on Radio Broadcasting operation.

It is not much fun, nor very noble to be a struggling victim of societal priorities. Some venues, such as UNIT/PITT projects (formerly known as the Helen Pitt gallery) deal with this problem of precarity by breaking out of the walk-in, white-walled, exhibition space. They have been supporting more and more work that does not, “require the four walls of a conventional gallery, including broadcasting, public processions, publishing, street posters, lectures, screenings… and performance.” (UNIT/PITT, 2018). Walking by the Save on Meats on Hastings, I was thrilled to see that they’ve renovated a tiny slice of their storefront into a full-on radio studio! Who’s to say that an art space can’t be whatever you’re able to make happen in the moment? Ephemeral programming is exciting because you never know what’s coming next or what is in the works. The programming may be more ‘up-to-the-minute’, and therefore more reactive and responsive to a community’s needs. As an artist or audience member, it makes you feel that you’re a part of something unpredictable: an adventure.

Street Art in Robson Square (Spray-foam adhesive and 3D Print)

If an arts venue can embrace the endless possibilities the form an artwork can take, art becomes that much closer to ‘real life’, and the viewer can participate rather than just spectate. ARCs are not only ridding themselves of the responsibility of keeping house when they explore these more spontaneous forms of art, they are also challenging the traditional notion of the gallery space as the standard for art exhibits. When artists pop up in these eventful bursts, they are creating movement outside walls rather than exclusivity within them. If contemporary art can be anything, does it need a gallery to exist? The type of work that UNIT/PITT is now focusing on can challenge commercial notions of the art object as a possession or commodity. Work that cannot be commodified cannot be absorbed or tainted by market demands. Ephemeral works can also serve well to carry ideas of decolonization, a concept that is becoming increasingly popular with an increase in indigenous scholarship. Could painting and sculpture be just as effective in off-site or temporary locations? Are ARCs destined to stop clinging to space in gentrified neighbourhoods like loose teeth in sore gums? Does the cutting edge of art beg to leave security behind?

The flipside of this is that UNIT/PITT has been putting on great programming out of a walk-in venue for 42 years. Instead of choosing freely to move on to this change in programming, they were forced out, pleading for small donations on the way. Yes, they are making the most of their situation by looking for a chance to adapt, but the bottom line is that it wasn’t possible for them to maintain a gallery. Temporality speaks of the ability of small-scale artists to respond to modern times, but could it also be a symptom of their inability to gain the respect permanence allows?

A work by Ken Lum in 221A’s Off-Site gallery “Semi-Public” is impossible to avoid by occupying a vacant gravel lot in Chinatown.

Architectural illustration for the proposed new Vancouver Art Gallery Location

Image source : https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/art-and-architecture/is-no-news-good-news-for-the-new-vancouver-art-gallery-building/article34499456/

It is understandable that there are only so many resources to fund fine arts, that there is a degree of competition between centers and that not every initiative can be able to succeed. There are other things that our government must fund outside the arts. However, it really put into context for me where the power lies when I visited the Vancouver Art Gallery to discover that they are almost ready to undertake their $350,000,000 move to a brand-new location which would make the already Colossal space more than twice as big (at 310,000 Sq-ft floor area) and would also end up doubling the VAG’s year to year budget (a lot of which is funded by the government). When you consider the fact that in 2010, to run 78 Artist-Run Centers across the entire country of Canada, the amount expended was just over $14,000,000, just barely enough to maintain the basics, this seems startlingly excessive. Some provinces like Nova Scotia spent less that $200,000 on ARCs in 2010. I can only imagine how powerful artist-run initiatives might become if they were offered $350,000,000.

Large art galleries like the VAG are feasts to appreciators of the arts. I have seen artworks at big-name museums that I couldn’t possibly imagine accessing in any other way, artworks that I’ve read about in art history textbooks. There is something to be said for a global arts conversation, something which huge galleries like this undertake to bring to local audiences. Being able to walk in and see art of such a vast scope or importance can benefit students of the art as well as members of the public. There is quite a lot of research that goes into what is shown at the VAG, and their aims are loftier than any ARC could ever dream of. Despite all these benefits, my most recent times at the VAG were like being swallowed by a massive labyrinth. The first time I went it was on their weekly night where they provide free admission for four hours. The line was out the door and all the way around the block. Seeing as their regular admission is $24, I can see why so many people showed up on the free night. However, if this is the demand they have from those who wish not to pay admission, you’d think their priority with additional funds might be to offer free admission to some of this eager audience. I’m sure glad that I didn’t pay admission to any of the artist-run galleries I visited, or the fees might be out of my budget.

I didn’t have enough time to look at everything the first time I was at the VAG. The four story extravaganza featured Canadian landscape painting, Canadian photography heroes, Artists exploring cultural diaspora, a DIY audiophile room and DIY light installation, a huge retrospective of ‘the Cabin’ in culture, and an entire immaculate floor dedicated to paintings by Emily Carr (big surprise there). I had to return a second time to take this all in and even then the security escorted me out before I had time to do more than glimpse at most displays.

Although I found (and have always found) the exhibits at the VAG to be thought-provoking, even life altering, it is hard to imagine showing work there at this point. Though I can dream of sweeping and mopping the marble floors at night, I might have to finish my BFA, get my MFA, show at MOMA, do residencies in the top ten art centers of the world, receive national awards and make work on the hottest recent topics before being permitted entry. The fact that we give such a prominent spot to this institute in downtown Vancouver, right in Robson Square, and run it at such a pristine level, shows that we live in a society that places an alarmingly high value on some kind of ‘art’ (or at least really like to look like we do). However, the idea of making this space twice as big makes my heart skip a beat. Is this the degree of extremity we’ve come to, where artists are in the lowest income bracket in Canada, and yet we centralize funds towards one giant Atropolis? When pleas are made to increase funding to the arts, many taxpayers complain that there is already plenty of funding in this area: regarding the VAG they would be right. However, I wonder what a society that placed a value on artistic work from the bottom up rather than as means to the end of an impressive global product might look like. The VAG is Big Enough.

Lineups at the VAG on Free Night

The current VAG in Robson square

Expecting an ARC to have a fraction of the public outreach that a massive gallery could is out of the question. Although ARCs do make continuous effort to reach out to the public and increase their audience, they simply do not have the budget to increase their marketing or employee-base and therefore cannot be expected to carry the burdens of public value that art giants can afford. Thinking critically about contrasting an institution like the VAG to Vancouver ARCs, I am led to believe that the way we support the arts in our society is systemically flawed, and that we might be afraid of the power art might hold when it maintains a distance from governing bodies rather than being their poster-child. This is a topic I would like to explore further.

Even in shopfront style ARCs, seeing art is not a guarantee. Unfortunately, I arrived during the one week in the year where every Vancouverite takes a vacation. One member of 221A said it was the longest vacation he had a chance to take in 13 years. A lot of the spaces I visited were between shows and there was no art on view (although there may have been artists-in-residences in the basement working away). I barged into spaces that were technically closed to badger people into chatting (and I’m glad I did). Some were too closed to find anybody, like the Gam Gallery, while others, like Fillip publishing, don’t operate a gallery space but instead publish writing on art and other subjects. The Toast Collective holds brunches and spontaneous parties, none of which I managed to attend, though I tried. I went to a zine party at the Dynamo Arts Collective, but they are a collection of private studios and shows there are infrequent and sometimes by invitation. What I’m getting at here is that these spaces have cycles of their own, like organic entities, and that not all of them are 9-5, Monday to Friday operations. Sometimes you find out about one by visiting another, and so on. Having programming that is constantly changing also means a little bit of investment by the viewer in finding out what is on, when its’ on, asking around and getting involved. I personally find it adventurous and exciting to have to do a little running around, and I’m happy that Vancouver has enough going on that there will always be something to experience. It is easy to see how working your way into the art scene of a big city goes beyond the skills they can teach in art school, and far from formulaic.

the OR Gallery

Not every venue has a sad tale to tell. An attendant at the Or gallery informed me that they’ve had no traumatic events in their history. Started in the 70s as a curatorial residency, the curator would live in an apartment next to the Or with the job of filling the gallery with artists’ work for a year. Although they no longer do this residency, the Or can program painting, sculpture as well as video in their exhibition space with the help of a full-time curator. They operate a small bookshop near the entrance. The Or has been in the same great location on Hamilton Street for 10 years now, and the staff had nothing to say of having to leave. I found exactly what I had hoped to find: cool art in a downtown center that you could walk right in and get involved with. One thing I will say of ARCs is that I was always greeted with a warm reception, and by someone deeply involved with the topic. I paid to attend nothing, and my entertainment for the week was entirely free. The staff I found inside were eager to offer additional information and new perspectives. It is rare to say all these things of almost any other urban space that comes to mind, other than the library.

I found an amazing show on in Chinatown’s Access Gallery (operating since 1991) which was also experimenting with a curatorial residency. The show challenged ideas of identity, included multimedia-work, and had a great tear-off essay on the wall instead of tombstones next to each piece. The great thing about the arts is that unlike other professions, they do not have a protected body of certified knowledge, anyone can access it. I thought this was exemplified by this curator’s work in their essay, which you could walk in and literally rip off the wall for free. The head curator at Access told me that they aim to both show work from up-and-coming artists and maintain a standard that is suitable for international professionals, indicating that they have somewhat institutional ambitions. I thought this was a great combination as showing in the same gallery as world-renowned work could be a game-changer for an artist at access that was having their first show or still trying to get their name out there.

Access Gallery Chinatown

A highly effective model for an ARC seems to be Vancouver’s Cinematheque, a local cinema started in the 70s that has occupied its downtown space since 1985. I was surprised to see that most of the films they show are eclectic or rare. From international directors that only film buffs have heard of, to independent documentaries, to film noir gems, you won’t find a blockbuster in the Cinematheque. And yet, when a friend and I went to see some funky Polish Claymation, the place was packed with people. After talking to a board member at the box office, it seems that part of the reason why the Cinematheque can program what they see as ‘essential cinema’ is because they know how to get along with the other niche cinemas in Vancouver. While the Rio theatre has all the cult classics and blockbusters covered, Vancity theatre also shows alternative films. The Cinematheque must strategize what section of the city’s film audience it will appeal to which is a great example of the natural organizational processes that happen when there is an abundance of arts venues in a city. Instead of viciously competing, there is a trend of arts centers to compliment or even collaborate with one another, much like organisms in a rich biodiversity.

The Cinemateque

Upon giving it some thought, another reason why the Cinematheque might be so secure (able to show more than 500 curated film exhibitions annually) is that what they offer doesn’t take up physical space. They don’t have to pay artist fees or the shipment, installation, and removal of work and sometimes putting on a new show is as easy as pushing a button. People are also accustomed to paying an admission fee for movies as they are part of popular recreation. Although the price of admission remains reasonable, The Cinematheque can then bank and budget all this revenue. They are also largely volunteer run and there seem to be a large amount of film appreciators in Vancouver what with it being ‘Hollywood North’ and home to the Vancouver Film School. Although its reason for being so successful may be largely due to the abilities of movies to act as an ‘end product’, the Cinematheque is still an awesome environment to experience art.

VIVO Gallery Space

Although there is little archiving done in artist-run centres due to lack of resources, one ARC VIVO maintains and makes use of a precious archive. Incorporated in 1973 as the first video exchange library, VIVO protects, collects, curates and distributes historic Canadian and International film that might otherwise be lost to the sands of time. Individuals can go in and access their libraries as well as take out and use equipment. Their industrial gallery space has also been home to everything from ear-drum exploding experimental noise to the intimate deep listening sessions of Quiet City. They are welcoming to Intermedia practices and have resources to show work that incorporates different digital technology.

Inside the Gallery Gachet

The work of one ARC has literally brought tears to my eyes. A one of a kind ARC that has been located in East Hastings for 25 years, the Gallery Gachet aims to debase some of the stigma around mental health issues. Named coyly after the doctor who helped Van Gogh in the last years of his life, the Gachet was started by a group of artists recovering from struggles with mental health who lacked a platform for their unique voice. None of the original members are present in the organization today, which is a trend I’ve noticed in a number of ARCs. It is interesting that an ARC is something that can be passed down from one group of people to the next as it is always the sum of many participants rather than one person’s vision.

East Hastings holds the postal-code with the lowest off-reserve income in all of Canada. 20% of the population of those that live there are artists, and it is internationally famed for its overflowing community of marginalized people and folks with substance dependencies. Hastings is an easy site to make ‘poverty porn’ and has become a symbol of those that have ‘slipped through the cracks’ of public systems. However, the Gallery Gachet does not contribute to the lens of dehumanization with which one often views East Hastings and offers a platform for the voices and artistic development of those that live there. When my friend Zack and I walked in the doors, we were immediately greeted by a busy art-making meetup and a host of board members who talked with us for hours of their experiences in the gallery. They even offered a binder for me to read which contained an overall mandate for running the centre and other important documents around which they are based. Another visitor to the gallery offered me tapes and cleaning equipment for my outdated DV camera. When we attended a book launch show for some poetry made by a self-advocate with down syndrome, we were greeted again as close friends.

Although it seems a shame to emphasize an artist’s disability when describing them, it is important in describing the Gachet in that they joyfully support the work of people who truly are excluded from most facets of the art world, and they do so with seriousness and professional standards. Much of the work made by artists that show there is superb regardless of the artist’s background. A jury meets once a year to select upcoming shows that is made up of 2 members from the ‘collective’, 2 from the gallery, 2 members of the community, and 2 people outside the community. All exhibition selections are consensus-based. The Gachet seems to be focused on finding solutions rather than problems. From questions like, “how could we make art accessible to the blind?” to, “are these power dynamics as helpful as they could be for all involved?” the gallery is in a constant process of change that large institutes are often criticized for being too inflexible to achieve. Although it is flawed to believe that art could be a catch-all solution to complex problems, and it is often employed as a solution to problems, the Gachet focuses more on showing and hosting people’s art than on placing heavy expectations on what art needs to accomplish. In this way they manage to stay true to the original radical agenda of ARCs.

Unlike most ARCs, the Gachet is funded by the health system. In 2015 the Provincial Ministry of Health imposed funding cuts on the gallery that amounted to more than half of their overall budget. When I visited them, they had recently moved from their old location to a new one couple blocks away. The nature of their work is best operated out of a permanent gallery and it is important that they can maintain one in Hastings. The Gallery Gachet remains my favorite Artist-Run Centre. I applaud them not for doing the work of a ‘charitable organization’, but for staying true to some of my favorite qualities of artistic work which is open-mindedness, the challenging of established perceptions, quality of life, and the valuing of humanity.

Rear entrance to the current Red Gate Space

Again, parallel galleries that don’t meet the criteria of ARCs are not eligible for their funding. The Red Gate venue, which had recently been evicted from East Hastings and forced to move to Main street combines music and art to form a counter-culture hub. I visited during a show where I could dance to noisy bands and order beers, then go into the next room which was a white, well-lit gallery and look at an exhibit titled, “CUIR: Latino American gazes on queerness”. When talking with a person heavily involved with Red Gate who will not be named, I learned that the Red Gate is having an equally tough time making their rent at Main Street which is over $10,000 a month, and without the incessant participation of volunteers, they are at risk of going under. Although I couldn’t picture a group of UBC MFAs doing a critique of the gallery (there was a comfy couch under the work in the gallery, no attendant, it was presented in a DIY fashion, the subject matter was verging on kitsch) how can you say that the Red Gate is not a home for alternative artistic practices and voices? And yet wading through the bureaucratic processes of being considered an ARC seems impossible for the Red Gate which is truly DIY. The Red Gate is apparently very open about who is allowed to jam there, play there, show work there. Their only demand is that you abide by some ethical rules posted on the walls including respecting each other and not being hateful.

A place like the Red Gate is extremely rare in Vancouver, in fact it is the only place I could find that attempts what it does. If with all our research into funding the arts, we are unable to develop policies that allow a place like the Red Gate to securely exist, what is the use of applauding more ‘professional’ Artist-Run Centres? It makes me think that instead of demanding that all cultural workers twist and bend themselves to submit perfect, white applications and reports to the CCfA, maybe some representatives from the CCfA could go in-person to venues like the Red Gate and see for themselves what an important role is filled by their presence and energy.

Another artist collective and gallery, Duplex, is in a similar risky spot. I only learned about Duplex by reading Discorder magazine, and not by visiting ARCs. As the article on Duplex says of their location, “it would be impossible to locate without direction unless you knew what their tiny duplex sign meant,” (Colbourne). While dealing with water leakages and electrical problems, Duplex manages to house the studios and workings of nearly forty artists. Despite being only able to, “compensate artists with what they earn through bar sales and tips, and through the gift of their own labour as organizers”, members of Duplex can reserve a lot of their energy to work on art rather than writing grants and maintaining the standards of a government-funded “Artist Run Centre”.

A collective like Duplex seems like an ideal place I would like to make art in but their cooperative model might not meet the needs of all galleries and centres. However, they do seem far more similar in their model to the original radical ideas of the “Artist-Run Centre” than do the more professional galleries. They have the freedom to change shape according to their needs as well as to display radical work. And yet, under our current funding models, securing Duplex with funds is very complicated.

So are ARCs worth protecting and if so, why? Sure, they make the dreams of individual artists come true and provide inspiration for fine art appreciators, but do they really fill a role in society at large? Are they worth the small sum that gets devoted to them or are they a model rooted in outdated ideas? It can be suffocating to put pressure on ARCs to contribute to ‘public good’ the way different publicly-funded organizations might. There are no measuring devices to determine the depth of impact that art can have. However, there are tangible contributions to the public that we can validate artist-run-centres as being effective in providing.

- ARCs train artists and curators, providing opportunities, internships, and communities for those just starting out to those well into their careers.

- The quality of ideas and conversations had there, such as the books one can access in the Pollyanna library of 221A, are arrived at through lifespans of experience and research. Members of the public can go in and gain free entrance to dialogue that is taking place on global and local scale as well as ideas that couldn’t gain agency elsewhere

- ARCs are run largely on volunteer labor and all those involved are passionate about the cause.

- ARCs put on workshops, often involving children and schools and provide affordable education.

- ARCs like Vivo or the Centre for Art Tapes (in Halifax) or FAVA (in Edmonton) provide access to expensive and specialized equipment

- ARCs build on and help one another, working collaboratively at small scales to build somewhat of a network.

- ARCs often rent out their spaces when not in use rather than leaving them vacant

The main problems with ARCs or reasons why they are insufficient at encompassing alternative practices may be that with pressures to professionalize it is not clear whether they really represent a parallel to gallery systems. When public galleries, university galleries and ARCs come to resemble each other in what they show, it is easy to see what is funded in the arts as what best fits into application models. It seems that the initiatives coming out of people’s garages and rundown buildings may be more effective as ‘alternative artistic spaces’. Even when it comes to professional art spaces that may require an administration team why do we have to pool power in Fine Art Monoliths? An arts ecology that includes smaller scale galleries like ARCs can better achieve diversity in the professional arts than the ever-expanding VAG can. If we are to continue supporting ARCs in their bureaucratic form, we should provide them with more secure space and a budget that doesn’t force the employees there to work overtime, make awkward compromises, and relocate. Providing a respectable permanence would make the most out of the funds we invest in institutionalized ARCs.

When it comes to truly artist-run, non-commercial collectives of fine artists, it seems we are still lacking in ideal ways to fund their work. It is a shame that artists not connected to institutions must take on the burden of not only educating themselves, making their work, and purchasing supplies but also in forming some sort of platform for their work out of thin air. That being said, the cultural shifts that have taken place since the seventies are not something that can be addressed merely by ‘throwing money’ at the arts. Still, if we truly do value the arts in society and want for them to achieve their full potential, we would be wise to reward the tireless labor of the devoted people that build our arts communities and ‘trickle down’ some water on those sprouts struggling to grow. We have seen the payoffs of allowing artistic work to take root in the history of Artist-Run Centers, and we can create it in our future by allowing artists to better mobilize within society. That is, to me, what would make our cities ‘World-Class’.

-Cat Jones

This project was supported by the Student Engagement Grant of Macewan University

SOURCES

- Barber, Bruce. “ARC to ICA, or Whatever…”, Concerning Artist Run Culture, YYZ Books, 2008. p22

- Canada Council for the Arts. The Distinct Role of Artist-Run Centres in the Canadian Visual Arts Ecology, 2011, Macewan University Catalog

- Colbourne, Esmée. “Another Hole in the Wall”, Discorder Magazine, June 2018.

- PAARC: The Pacific Association of Artist-Run Centres, 2014 arcpost.ca, http://arcpost.ca/file_download/43/

- Shier, Reid. “Do Artists Need Artists Run Centres?” Vancouver Art and Economies , Arsenal Pulp Press/Artspeak, 2007.

- Tayler, Felicity. “Artists’ Publications, Artist-run Centres and Alternative Distribution in Canada”, Art Libraries Journal, 2005, Vol. 30 Issue 1, p29-36.

- UNIT/PITT, “An Announcement of Changes Coming at UNIT/PITT”, 2018 https://www.helenpittgallery.org/updates/an-announcement-of-changes-coming-at-unit-pitt/

Links to Art Projects Mentioned :

http://www.thecinematheque.ca/

https://www.contemporaryartgallery.ca/

https://www.facebook.com/DynamoArts/

Feminist Electronic Art Symposium

http://gachet.org/

International bird Parade

https://www.thejamesblack.gallery/

Vancouver Outsider Arts Festival

http://www.cacv.ca/programs/vancouver-outsider-arts-festival/vancouver-outsider-arts-festival-2018/?

SUM Gallery :

https://queerartsfestival.com/about-sum-gallery/

The Toast Collective

http://thetoast.org/

UNIT/PITT

https://www.helenpittgallery.org/

Western Front